At Deir Al Bahri, the eyes first focus on the dramatic rugged limestone cliffs that rise nearly 300m above the desert plain, only to realise that at the foot of all this immense beauty lies a monument even more extraordinary, the dazzling Temple of Hatshepsut. The almost-modern-looking temple blends in beautifully with the cliffs from which it is partly cut – a marriage made in heaven. Most of what you see has been painstakingly reconstructed.

Continuous excavation and restoration since 1891 have revealed one of ancient Egypt’s finest monuments. It must have been even more stunning in the days of Hatshepsut (1473–1458 BC), when it was approached by a grand sphinx-lined causeway instead of today’s noisy tourist bazaar, when the court was a garden planted with exotic trees and perfumed plants, and when it was linked due east across the Nile to the Temple of Karnak. Called Djeser-djeseru (Most Holy of Holies), it was designed by Senenmut, a courtier at Hatshepsut’s court and perhaps also her lover. If the design seems unusual, note that it did in fact feature all the things a memorial temple usually had, including the rising central axis and a three-part plan, but it had to be adapted to the chosen site: almost exactly on the same line as the Temple of Amun at Karnak, and near an older shrine to the goddess Hathor.

The temple was vandalised over the centuries: Tuthmosis III removed his stepmother’s name whenever he could; Akhenaten removed all references to Amun; and the early Christians turned it into a monastery, Deir Al Bahri (Monastery of the North), and defaced the pagan reliefs.

Deir Al Bahri has been designated as one of the hottest places on earth, so an early morning visit is advisable, also because the reliefs are best seen in the low sunlight. The complex is entered via the great court, where original ancient tree roots are still visible. The colonnades on the lower terrace were closed for restoration at the time of writing. The delicate relief work on the south colonnade, left of the ramp, has reliefs of the transportation of a pair of obelisks commissioned by Hatshepsut from the Aswan quarries to Thebes, and the north one features scenes of birds being caught.

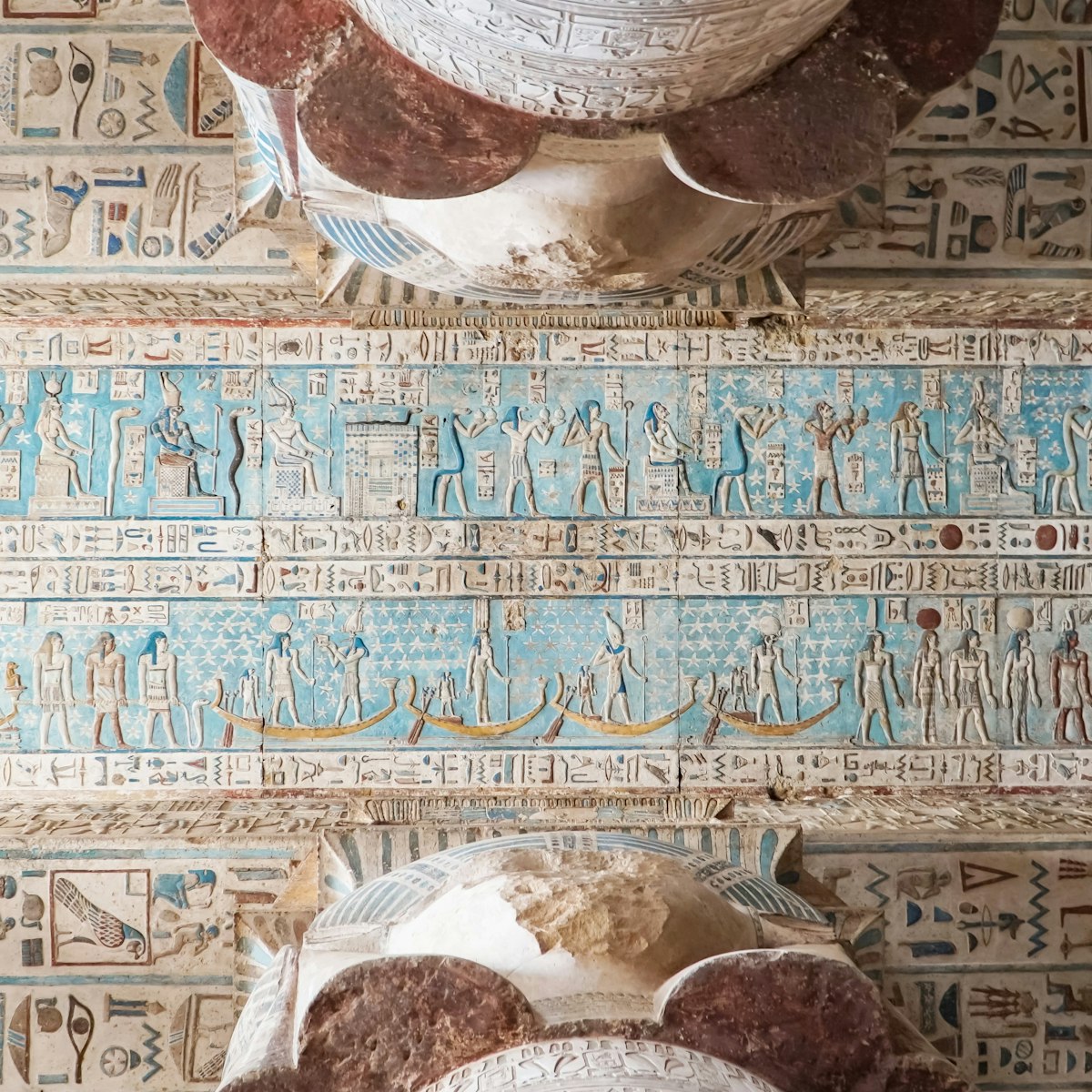

A large ramp leads to the two upper terraces. The best-preserved reliefs are on the middle terrace. The reliefs on the north colonnade record Hatshepsut’s divine birth and at the end of it is the Chapel of Anubis, with well-preserved colourful reliefs of a disfigured Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis III in the presence of Anubis, Ra-Horakhty and Hathor. The wonderfully detailed reliefs in the Punt Colonnade to the left of the entrance tell the story of the expedition to the Land of Punt to collect myrrh trees needed for the incense used in temple ceremonies. There are depictions of the strange animals and exotic plants seen there, the foreign architecture and landscapes as well as the different-looking people. At the end of this colonnade is the Hathor Chapel, with two chambers both with Hathor-headed columns. Reliefs on the west wall show, if you have a torch, Hathor as a cow licking Hatshepsut’s hand, and the queen drinking from Hathor’s udder. On the north wall is a faded relief of Hatshepsut’s soldiers in naval dress in the goddess’ honour. Beyond the pillared halls is a three-roomed chapel cut into the rock, now closed to the public, with reliefs of the queen in front of the deities and, behind the door, a small figure of Senenmut, the temple’s architect and, some believe, Hatshepsut’s lover.

The upper terrace, restored by a Polish-Egyptian team over the last 25 years, had 24 colossal Osiris statues, some of which are left. The central pink-granite doorway leads into the Sanctuary of Amun, which is hewn out of the cliff.

On the south side of Hatshepsut’s temple lie the remains of the Temple of Montuhotep, built for the founder of the 11th dynasty and one of the oldest temples thus far discovered in Thebes, and the Temple of Tuthmosis III, Hatshepsut’s successor. Both are in ruins.